The Historic Columbia River Highway

in Oregon

The Historic Columbia River Highway

in Oregon

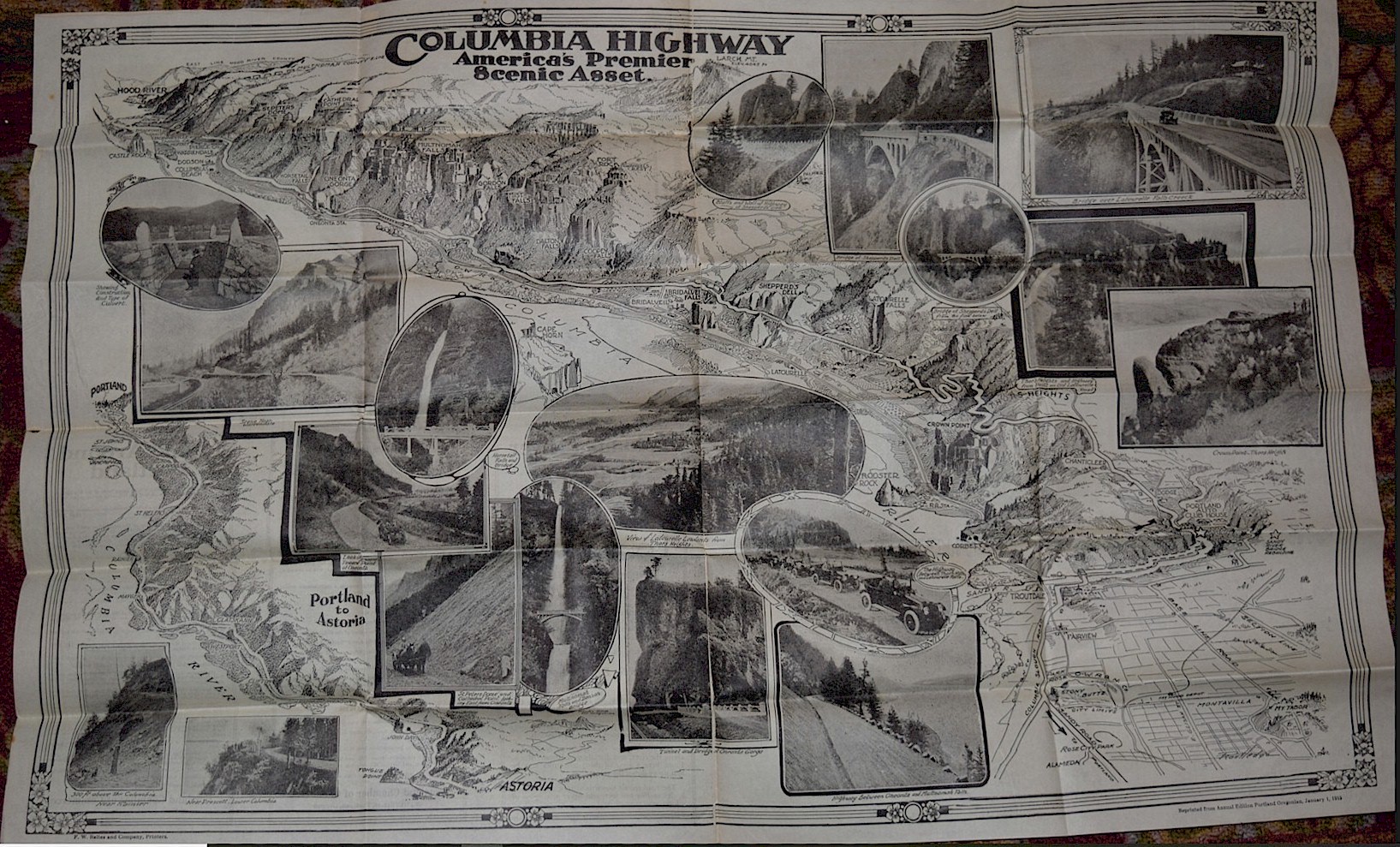

The Columbia River Highway

By Fred Lockley 1928

Material submitted by Jeffery A. Fox - 2022

In the spring of 1856 a wagon road was built from Bonneville to Cascade Locks, a distance of about six miles. It was not till the fall of 1872 that the Legislature decided to appropriate $50,000 to build a wagon road from the mouth of the Sandy River in Multnomah County, through the Columbia River Gorge to The Dalles. This appropriation was exhausted and the road was not half built, so in October, 1876, the Legislature made another appropriation of $50,000 to complete the road. The road, if road it could be called, was narrow, full of sharp curves and the grades were so steep that it was often necessary to double teams to pull up the hill.

In winter the road was often impassable, on account of the deep mud. However, it was an improvement on the old trail used by the emigrants. In the 1840's and early 1850's, when the emigrants arrived at The Dalles, they usually drove their cattle to the Willamette Valley by the Old Indian Trail and put their wagons and their women folk on rafts, making landings at the mouth of the Sandy River in Oregon or at Vancouver, Washington. In 1862 the first railroad line ever built in the Cascades, went down the Columbia River between Bonneville and Cascade Locks, and a small engine known as the Oregon Pony provided the motive power for the railroad.

When the Oregon-Washington Railroad and Navigation Company built their line along the south bank of the Columbia River in 1883, they used the right of way of the wagon road which had been built between the mouth of the Sandy River and The Dalles and for thirty years the settlers had to depend on the railroad or boats to get into or out of the country. In 1912, Samuel Hill conceived the idea of building a scenic boulevard or highway along the banks of the Columbia River.

For many years Mr. Hill had been spending his time and his money freely in advocating good roads. He enlisted the cooperation of C. J. Jackson, the publisher of the Oregon Journal, of Simon Benson, a millionaire lumberman of Portland, of John B. Yeon, another wealthy and public spirited citizen of Portland, of Rufus C. Holman, county commissioner of Multnomah County and of a number of other public spirited and progressive citizens of Portland.

Through lectures with lantern slides showing the beauties of the roads in Switzerland and elsewhere in Europe, with articles in the various Portland papers, and through personal talks, Mr. Hill enlisted the interest of a group of men who, in the summer of 1912, went as far as they could by automobile and then went on foot to look over the proposed highway. Mr. Hill believed that if a highway were to be built, it should be built in the best possible manner, so he took with him Samuel C. Lancaster, an employee of the road department of the United States Government and also Maj. H. L. Bowlby, another noted engineer, to Europe to investigate the roads in Switzerland, France, Italy and elsewhere in Europe.

He did this at his own expense, so that they should be able to take advantage of the best engineering minds in Europe. Upon his return from Europe, Mr. Lancaster was appointed consulting engineer of the Columbia River Highway and all of the engineering work preliminary to the pavement construction was under his supervision. John B. Yeon, who had accumulated a fortune in the lumber camps of the Northwest, was appointed roadmaster without a salary.

From the fall of 1913 to the fall of 1915 John B. Yeon was on the job all of the time and worked as hard as any of the men under him, and received no other remuneration than the approval of his friends and associates. Simon Benson, who had also made a fortune in logging operations in the Pacific Northwest, helped finance the highway had purchased and presented to Multnomah County, what is known as Benson Park. The 300 acres he presented to the county included the far-famed and picturesque Multnomah Falls and also Wahkeena Falls.

Multnomah County spent $750,000 in the construction of the Columbia River Highway and then voted a bond of $1,250,000 for paving it. Six hundred and forty-nine thousand six hundred and thirty-two square yards of pavement was laid, at a cost of $1,039,131.80. All of this was done without state or federal aid. From Portland one can reach the Columbia River Highway either by way of the Sandy Boulevard, Base Line Road the Section Line Road or the Powell Valley Road.

The maximum continuous rise is less than two miles and is between Latourelle and Crown Point, the total rise being about 500 feet. Between Portland and Chanticleer the total rise is 875 feet. Nowhere is there a grade of over five per cent. The highway is 24 feet wide. There were seventeen concrete bridges and viaducts with a total length of 3,699 feet in Multnomah County. The Columbia River Highway had extended from Seaside on the shores of the Pacific, through the Cascades and on into eastern Oregon, where it connected with the highway that continued on to the shores of the Atlantic.

In continuing the Columbia River Highway from Portland to the Sea, Clatsop and Columbia counties voted bonds to the amount of $800,000 for the construction of the connecting link between Portland and the sea. This road was opened in August, 1915. The highway between Portland and Astoria passes over the coast range of mountains, but nowhere does the grade exceed 5 per cent, and the highway was in no place less than twenty-four feet in width.

The engineering costs were 2.5% of the amount expended. All of the preliminary work of the highway was under the direct supervision of Samuel Hill, Maj. H. L. Bowlby and Samuel C. Lancaster. J. B. Yeon, volunteer roadmaster, had charge of all highway construction. For the first fifteen miles eastward from Portland, the Columbia River Highway passes through a level, fertile and beautiful farming country, somewhat reminiscent of the fertile fields of old England. After crossing the Sandy River the former county road was abandoned on account of its steep grades.

A new roadway was cut along the bank of the Sandy River for more than a mile-and-a-half, necessitating the cutting down of a rocky bluff more than 200 feet high. In describing the structural features of the highways, A. A. Rosenthal says:. "After crossing the Sandy River, the highway begins a gradual ascent to the Columbia River, where, at Crown Point, an elevation of 700 feet above the river, is reached. The bluff is vertical and when the work was begun it was necessary to suspend the men with ropes until a foothold was obtained.

The niche cut into the bluff was 24 feet wide and the outer edge was protected by a stone wall or fence. The road winds its way in graceful curves around the bluff to what is known as Crown Point at an elevation of 700 feet. Nothing here obstructs the view up the gorge for thirty-five miles or down the river twenty-five miles to where the Willamette empties into the Columbia. Here a walk 8 feet wide on a concrete wall 42 feet high formed a visitors' observation promenade.

From Crown Point the road winds around the bluff to Latourell Falls, a distance of two and a quarter miles, making a drop of 600 feet in this distance. To preserve the maximum grade of 5% it was necessary to have the road form a figure eight paralleling itself five times. The old wagon road down the mountainside in several places had a grade of 20% and in no place was it less than 10%. The first concrete bridge of the highway was Latourell Falls. It is 240 feet long with three spans, and is 100 feet high. From Latourelle to the second bridge at Sheppard's Dell is one and a half miles.

This bridge is 130 feet above the abyss and has a single 170-foot arch span. Just beyond this point a jutting rock of peculiar shape, called the Bishop's cap, obstructed the road and a half tunnel was blasted through it, maintaining the established width and grade and making a semi-circular sweep of 200 feet radius. At Bridal Veil Falls the bridge, 110 feet in length, crosses directly over the falls. From here the road passes a number of waterfalls, the most prominent being Coopey and Mist.

The next point of interest is Benson Park, named after the donor. The Wahkeena Falls just beyond, the character of the ground and the proximity of the O. W. R. and N. Co. railroad tracks necessitated the construction of a viaduct. A mile from this point, in Benson Park, are the famous Multnomah Falls more than 900 feet high, the second highest in the United States. A highway bridge and a foot bridge of stately design and dimensions were built by Mr. Benson immediately below the upper falls and over the chasm cut by the rushing waters.

Near here the tracks of the O. W. R. & N. Co. occupied all the available space between the river and the mountain side. The danger of slides precluded any excavation, so that the difficulty was overcome by the construction of the longest viaduct on the highway. To minimize the danger of injury from snow or earth slides, the viaduct was built with a sufficient space between it and the hillside to permit slides to pass without disturbing the structure. All viaducts were 20 feet wide with a concrete protecting wall on the outer edge, enhancing the general effect of the artistic design.

The next point of interest is Oneonta Gorge, two and three-tenths miles beyond Multnomah Falls. The Gorge is formed by two solid walls of rock several hundred feet in height and so narrow that the stream of water from the falls located one and one-half miles up the gorge takes up the entire width so that no room was left for even a foot path. At this point a cliff of solid rock several hundred feet in height barred further progress in construction. The railway track was using the only available space for a roadway and the depth of the river at this point, together with the danger of inundation at the recurrence of high water, precluded moving the tracks, so that it was necessary to pierce the obstacle with a tunnel 100 feet long.

One-half mile beyond this point is Horse Tail Falls, so close to the highway that the spray keeps the roadway moist. A handsome concrete bridge 60 feet high spans the creek. Seven miles beyond McCord Creek is crossed on a concrete bridge 360 feet in length. The bridge crossing Moffett Creek is 170 feet long and 75 feet above the bottom of the valley. The next point of interest is Bonneville, where the State Fish Hatchery and another concrete bridge are located.

Some very heavy construction work was necessary here where the road is cut into the bluff and attractive designs in resting places and viewpoints have been arranged. Eagle Creek is the last stream to be crossed by a bridge in Multnomah County. Its bridge is one of the most unique and beautiful of the Columbia River highway bridges and is of reinforced concrete faced with stone. It is a full centered arch with a span of 60 feet and a length over all of 144 feet.

All viaducts are 20 feet wide with the roadway supported on columns set 20 feet apart in rows 17.5 feet apart. The combined length of the eight bridges is 2,012 feet, the total cost of which was $89,220.50. The cost per square foot for deck surface varied from $1.25 for viaducts to $3.50 for high bridges. The total cost for grading of the Columbia River highway was $892,983.05 and for hard surfacing, $448,855. The cost of the highway in Multnomah County totaled approximately $1,500,000.

The construction of the highway through Hood River County in the very heart of the Cascade Range of mountains was financed by a bond issue and aided by the state in the piercing of Mitchell's Point, an insurmountable precipice, by a tunnel which cost $100,000. In speaking of the Columbia River Highway, Maj. Henry L. Bowlby, the former state highway engineer of Oregon, said;

"The Pacific Coast has proven to be a fertile ground for the growth of national highways. An immense territory with few existing roads, this is a paradise for a highway engineer, affording, as it does, an opportunity for him to put into practice the best there is in modern highway engineering. Our Pacific Coast states are separated from the main part of the United States by an almost impassable barrier. The Cascade Mountain Range is unbroken from British Columbia to Mexico, except in three places the Fraser River on the North, the Columbia River between Oregon and Washington, and the Klamath River between Oregon and California."

"It is along the Columbia River route that the Columbia River Highway has been built—a highway conceded to be one of the most notable scenic attractions of the Pacific Coast. The great gorge of the Columbia River provides some of the most magnificent scenery in the world. Its beauties have been portrayed by John Muir, John Burroughs, Joaquin Miller and many other noted writers. The Columbia River Canyon is so rugged that no attempt to build a road through it was successful until the project started in 1913."

In 1910 Henry Wemme, an early-day automobile enthusiast of Portland prepared and circulated a petition to have a road constructed from Bridal Veil Falls eastward to the Hood River County line. The survey provided for a narrow road with sharp curves and grades up to 9 per cent. By 1912 a little less than two miles of this road had been built east from Bridal Veil Falls. This had to be relocated and rebuilt in 1914 to conform to the standards established by the state highway commission for state trunk roads, which standards provide for a roadbed 24 feet wide, both in cuts and fills, with a maximum gradient of 5 per cent.

The minimum radius of curvature is 200 feet except in a few exceptional cases. In no place has a radius of less than 100 feet been used and whenever the radius of curvature is less than 200 feet the grade and the curve has been reduced at the rate of 1 per cent for each 50 feet in the reduction in the radius. Governor Oswald West in 1912, began experimenting with convict honor camps in building roads in southern Oregon. Simon Benson of Portland, donated $10,000 toward the construction of a road around the foot of Shell Rock Mountain in Hood River County.

This had always been regarded as an impassable barrier to a wagon road. The work done by the convicts in putting a roadway around Shell Rock Mountain called attention anew to the need of a Columbia River road. In 1913 the building of the Columbia Highway on its present magnificent scale was undertaken. The state highway department, which was created the same year, had charge of its location and engineering of all kinds required in its undertaking.

Oregon was the last of the Pacific Coast States to establish a highway department. Samuel Hill's influence was felt again in this matter. In February the members of the Oregon legislature were his guests on a trip by special train to Maryhill, his country estate on the Columbia River. He had built, at his own expense, several miles of modern hard surfaced road near his ranch, costing $120,000. After listening to an illustrated lecture on road building by Mr. Hill and inspecting thoroughly these roads, the legislature enacted the law providing for a state highway engineer and a system of state roads.

The State Highway Commission, thus created, secured the services of the writer as state highway engineer, and launched an extensive road building campaign. No money was available for the use of the department except $10,000 set aside for office expenses. A campaign of education was started with the object of inducing the counties to vote bonds to build trunk roads under the direction of the State Commission. The first to take advantage of the new law was Jackson County.

On July 3, 1913, this county turned over to the state highway department the location and construction of the Pacific Highway in that county, and raised $500,000 from a bond issue for this purpose. Counties on the Columbia River were the next to feel the effect of the state wide campaign for good roads. Clatsop, Columbia, Hood River and Multnomah counties raised altogether $2,385,000 for the construction of the Columbia Highway. On July 26, 1913, the board of county commissioners of Multnomah County, under the leadership of its chairman, Rufus C. Holman, appointed an advisory committee to advise them on matters connected with the new departure in modern road building.

On September 24, 1913 the county board turned over to the state highway department all engineering connected with the Columbia highway in that county and set aside $75,000 to the order of the state commission for this purpose. An assistant highway engineer was placed in charge of each of the different units. S. C. Lancaster was appointed assistant highway engineer and placed in charge of the work in Multnomah County. Surveys were made and construction started in October, 1913.

A feature of the construction in Multnomah County was a "Millionaire" Roadmaster—John B. Yeon, one of its leading citizens, who had given more than two years of his time free to the public and had an active charge of the construction of the county roads. All of the road construction, except the bridges and hard surfacing, was done under his direct supervision by foremen and gangs of laborers. The bridges and viaducts were built and the pavement laid by contract.

The cost of the Warrenite pavement was approximately $15,000 per mile. The bridges and viaducts on this section of the highway were worthy of special mention; reinforced concrete construction being used in all cases. Many of the structures are of novel design, an effort having been made in each case to fit the structure into its natural setting and to make the completed bridge a work of art as well as an example of the best economical engineer practice. The Latourelle Falls Bridge is a concrete arch structure 312 feet long and 97 feet high to the grade of the roadway.

It carries a 17 foot driveway with a cantilevered sidewalk and railing on each side, which bring the total width of the structure to 25 feet. The most noteworthy feature of this bridge is its lightness, the total amount of concrete above the ground being only 560 cubic yards. One of the factors making necessary a light structure at this place was the difficulty of securing a firm foundation. The underlying bedrock is covered with a layer of silt and boulders, having an average depth of 25 feet at the western end of the bridge and with a deposit of drift sand 50 feet deep at the eastern end.

The cost of building abutments and piers for a heavy bridge would have been very high under these circumstances. Notwithstanding the lightness of the structure the factor of safety was as high as that of any bridge on the highway and was above standard requirements. The total cost of the completed structure was $26,936.12. The Sheppard's Dell Bridge is a single span, reinforced concrete bridge, 150 feet long and 130 feet above the creek bottom.

The arch has a span of 100 feet and consists of two parabolic arch ribs 3 feet 2 inches square at the spring lines and 3 feet 2 inches wide by 2 feet 2 inches deep at the crown. The deck is carried by four columns on each end of each rib, spaced 10 feet center to center and by a solid spandrel extending 20 feet each way from the center. The bridge carries a 17 foot driveway and two 3 foot cantilevered sidewalks. Its total width, including the railings is 25 feet. Total cost complete was 810,763.07.

The bridge below Multnomah Falls is a five-centered concrete arch, with solid spandrels, the space over the arch barrel being filled with earth. The bridge is 67 feet long and the span of the arch 40 feet. Total cost $4,127.35. At two places the location of the highway at the base of the mountains and inside of a railroad track made it necessary to build viaducts or excavate an enormous amount of material. On account of the cost of such grading and the lack of a place to waste the excavated material, it was decided to build the viaducts.

These are two in number and have a total length of 1,260 feet, width of roadway 18 feet. In each case the roadway is carried on columns spaced 20 feet apart, longitudinally, and 17 feet 6 inches apart transversely. Both rows of columns are parallel to the center line of the highway, the columns on the side toward the hill being, of course, considerably shorter than those on the outside. The footings of the two columns in each bent are connected by an inclined strut which is capable of carrying the weight of the structure and is provided to insure against settlement of the upper footing. The approaches are held by retaining walls of dry rubble masonry. These viaducts cost complete $26.22 per lineal foot.

At Oneonta Gorge a concrete girder bridge was built eighty feet in length at a cost $2,498.36. Below Horsetail Falls a concrete bridge was built across Horsetail Creek. Length 60 feet, cost $1,819.70. A small concrete foot bridge was constructed over Lower Multnomah Falls, length 50 feet, cost $1,200. Across McCord Creek a concrete viaduct carries the highway for 360 feet-80 feet above the bottom of a ravine. The viaduct is supported by four-post towers, having girder spans of 54 feet between towers.

Two girders with crossbeams carry the two-way slab floor construction. Cost complete $17,653. The Tanner Creek Bridge is a concrete deck girder span of 60 feet with wing abutments 20 feet high. Floor beams between girders permitted of two way slab construction for the deck. For a distance of 180 feet on the highway above Bonneville, it was found to be cheaper to carry the road partly on a concrete viaduct and partly on the solid rock roadbed, rather than to cut the full road bed out of the vertical rock cliff which rises 700 feet.

Columns carried down to the face of the rocky cliffs support girders of from 20 to 30 feet span. The floor beams are carried at one end by the girder and at the other end are embedded in notches cut in the cliff. This construction saved the immense amount of solid rock excavation, which would have been necessary in excavating a roadway 24 feet in width. About 12 feet of the roadway is carried on the concrete structure and the balance on the cliff shelf. The same typical stone railing that follows the highway along the edge of the cliff is used on the viaduct.

The Eagle Creek arch is a three-rib half circle arch of 60 feet span, the deck being carried on spandrel columns and the entire concrete construction covered with a basalt rock veneer. The stone arch ring carries the stone spandrel wall. The rock arches and spandrel walls are tied to the concrete ribs by small steel hooks passed through loops embedded in the ribs. The abutments are made of dry rubble masonry. Cost complete $8,500.

The Moffett Creek Arch is probably the most unique of the concrete bridges on this highway. It has a clear span of 170 feet with a rise of only 17 feet. It is a true three hinge reinforced concrete arch bridge. The hinges are of massive cast iron with four and one-half steel pins to carry the load. This is the longest three-hinge concrete bridge span in the world. Cost complete $16,390.39.

The Columbia Highway in Oregon begins at Seaside, on the Pacific Ocean, in Clatsop County. It parallels the ocean beach for twelve miles and then cuts directly across the marshlands, a distance of twelve miles, to the City of Astoria. From Astoria, to the Columbia County line the highway extends in this county twenty-eight miles, which were graded in 1914. The county voted a bond issue of $400,000 on November 4, 1913. The surveys were started by the state highway department, October 16, 1913, and completed April 4, 1914, covering a location of forty-six miles, much of it through some of the heaviest standing timber of the North-west.

The contract for constructing the first section of twenty-eight miles was let May 11, 1914. Its cost, including grading and bridges was $300,000. It was in Clatsop County that the first section of the Columbia Highway was hard surfaced, two miles of Warrenite pavement having been laid in 1914, between Seaside and Gearhart. On Whidbey Mountain, twenty-three miles east of Astoria, and over-looking the mouth of the Columbia, the highway runs out of a forest of firs at an elevation of 700 feet to descend 650 feet on a five per cent grade along the face of the cliff.

The descent was accomplished by four wonderful hairpin curves, and yet the road was so located that a long sight line for the autoist was preserved on each curve. This was unquestionably the grandest feature of the lower section of the highway. From the crest an unbroken view was obtained up and down the river for a distance of nearly forty miles. Following the river towards Portland the highway passes through Columbia County for fifty-six miles along which course the most attractive scenic section which was the Beaver Valley unit, on which is located the beautiful Beaver Falls.

In February, 1914, Columbia County voted a $360,000 bond issue, which was turned over to the State Highway Commission for expenditure. The surveys, started October 17, 1913, were completed April 21, 1914, and construction began on May 17th of the same year. An indication of the character of the country through which the highway runs is shown by the cost of making the surveys in this county, the average cost per mile of located line being $239.15. Some of the heaviest standing timber of the Northwest was encountered on this section.

Multnomah County raised $1,250,000 by a bond issue to pay for its share of an interest in a highway bridge across the Columbia River at Portland. This county also raised $1,250,000 by another bond issue to hard surface the Columbia Highway and other trunk roads. The money for grading the road and building the concrete bridges was raised by direct taxation. In Multnomah County the highway had been completed and paved. At a distance of twenty-three miles from the city Crown Point is reached.

The road here is carried around the top of a rock cliff at an elevation of 750 feet above the river, on a curve of 110 feet radius. The central angle of the curve is 225°. On the outer edge of the road a 7 foot sidewalk had been built and is protected with a concrete railing 4 feet high. Latourelle Falls is passed at 26 miles and Sheppard's Dell at 27.3 miles. Bridal Veil Falls is 1 mile farther and Gordon Falls or Wahkeena (the most beautiful) Falls in Benson Park are 31.5 miles from Portland.

Multnomah Falls, the largest and grandest of the ten waterfalls encountered in this county, are a mile beyond Wahkeena Falls. A large park of 400 acres including the best of the falls and the most rugged of the landscape was purchased and presented to the public as a gift by S. Benson of Portland. Another point of especial interest is the Oneonta Gorge and Tunnel two miles from Multnomah Falls. The highway crosses the stream on a reinforced concrete bridge and passes immediately into a tunnel 125 feet in length.

The height of the rock cliff is 205 feet, the railroad is close to the face of the cliff and the river is next to the railroad so that a tunnel was the only solution to the problem. Horsetail Falls are a few hundred yards farther, and 40 miles out from Portland, the scenic three-hinged arch bridge over Moffett Creek is crossed. Twenty miles more the Mitchell Point Tunnel is entered and the City of Hood River is five miles farther east. Pendleton, the home of the "Round-up" is the eastern terminus of the Columbia Highway, distant from Seaside 363 miles.

A variation of rainfall of unusual degree is found on this highway. At Astoria, nearly 100 inches per year is the average; at Portland, 42 inches while at Cascade Locks the precipitation is 77 inches, and 60 miles farther east it is 15 inches per year. In the Hood River County the gorge of the Columbia widens out again above the Cascades, producing some of the grandest and most rugged scenery to be encountered in the world. At one point five miles west of Hood River City it was found that the most economical construction would be a tunnel through solid rock for a distance of 400 feet.

To have built over the point of rock using the maximum grade of 5 per cent would have required an additional mile of road. The State appropriated $50,000 to construct this section of the highway, 4,500 feet in length. Topographical conditions were right for a tunnel with windows cut out to the face of the rock cliff. A 200 foot viaduct of reinforced concrete was planned for the west approach. The tunnel portal at this end is short, the highway entering the face of a rocky nose.

At the east end the portal excavation is more than 100 feet long. There are five windows in the tunnel, each window being approximately 20 feet long and 19 feet high. The tunnel section is 18 feet wide and 19 feet high. The tunnel required very careful work on the part of the contractor, the specifications providing a bonus for carefulness in excavating the tunnel and window sections. The tunnel cost complete was $14,472.85; its actual length is 390 feet, giving a cost per lineal foot of $37.30.

The concrete viaduct approach at the west end cost complete was $8,550.30, its total length being 280 feet and its cost per lineal foot was $41.10. This high unit cost was due to the great length of the supporting columns required. This tunnel, it is claimed, excels the Axenstrasse on Lake Lucerne in Switzerland. The windows are protected by concrete railings and are recessed so to provide ample room for tourists to stand and view the Columbia River 150 feet below and the rugged shores of Washington on the opposite side.

Hood River County voted a $75,000 bond issue which was used in grading six and one-half miles of the highway in places where no road existed. The completion of these sections made it possible to open the Columbia Highway to traffic in August, 1915.

As the western terminus of the Lincoln Highway, the Columbia River section will inspire the transcontinental tourist with a feeling of pleasure and satisfaction that will repay him for the fatigue of the long trip and induce him to linger several weeks sightseeing and enjoying the climate of "America's Switzerland the Pacific Northwest."

From a 1920's Portland Chamber of Commerce

Brochure

Courtesy Jeffrey A. Fox

The Columbia River a Photographic Journey

Recreating the Old Oregon Trail Highway