The Historic Columbia River Highway

in Oregon

The Historic Columbia River Highway

in Oregon

Deschutes River to Umatilla

By Curt Cunningham

The Columbia River Highway between the mouth of the Deschutes river and Umatilla was 83 miles long. It passed through Biggs, Rufus, Arlington, Boardman, Irrigon and Umatilla. It also passed through lesser known places, which were nothing more than a boat landing for steamers or a station or flag stop on the Oregon Railroad and Navigation company's (O. R. & N.) line or both. The predecessor to the O. R. & N. was the Oregon Steam and Navigation co. (O. S. N.) which dates back to 1862 when it was just a small portage railroad on the Columbia hauling cargo around the rapids.

In 1879 the O. R. & N. was incorporated and a year later they built a line from Wallula and Celilo along the southern banks of the Columbia river. By 1882 the line reached Portland and they used the roadbed of the O. S. N. and The Dalles & Sandy River wagon road where it was needed. In 1896 it became a subsidiary of the Union Pacific, and in 1910 they became the Oregon Washington Railroad & Navigation company (O. W. R. & N.). In 1936 the company was absorbed into the Union Pacific system.

The lesser known boat landings and railroad stops along the old line were called; Miller Junction, Sherman, Spanish Hollow, Grants, John Day, Goff, Squally Hook, Quinton, Blalock, Boulder, Willows, Heppner Junction, Castle Rock, Peters, Messner and Coyote. Most of these little places along the old line were submerged along with the old railroad grade when the John Day dam was completed in 1971. The ones that were not submerged just disappeared.

In the November 7, 1915, and the November 25, 1917 issues of the Oregon Journal were articles about the boat landings which existed between Celilo and Umatilla, and the importance of a highway along the Columbia which could be linked to lateral roads which lead into the interior. This was so that products could be moved more efficiently. The Columbia River Highway was an essential factor in the open river campaign of the mid to late 1910's. In 1915 Fred C. Schubert, who was a civil engineer said in his report to the Open River association that; "Most of the wagon roads in the upper Columbia district between producing areas and the river are poor."

The 1917 article said that before waterway transportation could be developed, it was essential that a highway along the river, with branches reaching into the interior, be constructed, over which food products may be assembled at boat landings. No intelligent consideration of the problem of transportation, which was growing more serious every day in 1917 through the necessities of war conditions, could have been given without reference to the highway and its relation to every form of transportation, including water and rail.

The following were the boat landings that were reported in the 1915 and 1917 newspaper articles between Celilo and Umatilla and the distance they were from Portland; Celilo, 117 miles. There was no regular landing except that of the Oregon state portage railroad, which had a railroad incline and wharf boat but there was no wagon road to the incline. The old landing for Celilo, used in the early times, was about a mile upstream at old Celilo, where there was a good beach landing. There was a poor wagon road from the hills leading to this place. There was little prospect for river commerce, as all of the products went to The Dalles. The landings at Celilo and old Celilo would become submerged after The Dalles dam was completed in 1957.

Miller, 100 miles. In 1917 a railroad station called Miller was established a mile east from the mouth of the Deschutes river. It was named for either Thomas Jefferson Miller or his brother Charles S. Miller. The place was originally called Fultonville which was founded in the 1860's by Colonel James Fulton, and the small town lasted about 5 years. In 1922 a post office was established there also called Miller. By 1953 the post office and train station were abandoned.

Biggs, 124 miles. Was originally about a mile downstream from the current village. Biggs was the terminus of the Columbia Southern railroad. There was a small settlement there in 1915 and the boat landing was at Spanish Hollow, about one mile upstream. Spanish Hollow (Biggs Junction), 125 miles. There was a ferry operating between there and Maryhill on the Washington side which was established by Samuel Hill in 1915. The ferry was a link in the old Mexico-British Columbia road now called Highway 97. About 1921 the ferry was moved to Grants. Spanish Hollow had a good boat landing, but it was against the railroad grade, and the wagon road passed under the tracks and the road would be submerged at high water.

Sam Hill's Maryhlil Land company had acquired land at Spanish Hollow and owned some waterfront there, and in 1915 they made plans to construct a warehouse on the high ground above the railroad. They were going to load the boats by a series of chutes. There was also plans to to construct a paved highway 10 miles from Wasco to Spanish Hollow which was completed in the summer of 1915. Spanish Hollow today is called Biggs Junction and has hotels, restaurants and gas stations which serve people traveling on Interstate-84, U. S. Highway 30, and U. S. Highway 97.

Grants, 126 miles from Portland was a flag station on the O. W. R. &. N. This was the ferry landing for crossing over to Maryhill until 1962. Rufus, 129 miles. Was a station on the railroad, and the 1915 report said it was formerly a wheat shipping point on the O. W. R. & N. railroad before the Columbia Southern railroad was established. The report said that there was a poor river landing on a flat shoal beach with no prospects for river commerce. John Day, 133 miles. There was no settlement or business but it had a railroad station and a poor boat landing at the head of the rapids. There was a wagon road that went south down the John Day river canyon.

Squally Hook, 140 miles. Had a

railroad station and a fair boat landing. There was no business for boats and

had no access to the tributary country. Quinton, 143 miles. Quinton station was established in 1881 and was

at first called Quinns. It was named after a man named Quinn who was an

early settler at that place. The name was changed to Quinton in the early 1900's. Philippi canyon was originally known as Quinton canyon.

In 1903 a post office was established there and was named Brown after the postmaster Charles E. Brown but the name was rejected and it became the Quinton post office and operated until 1910.

From 1919 to 1925 another post office opened about a mile or 2 to the west

which was called Quinook. This name came to be from combining the names of Quinton and Squally Hook.

In addition to the depot, Quinton had a wheat warehouse near the tracks and

had a good landing on a sand bar between two rock bluffs. The 1915 report

said it was an old wheat shipping point used by water transportation and considerable wheat

continued to be shipped by river transport. Quinton had a small wheat platform at the

river and the construction of a warehouse on the river bank was contemplated.

It had a road from the hills which ran down a canyon to the river and

crossed the O. W. R. & N. track. This may be today's Quinton Canyon

Road. The report also said that the status to the river was doubtful.

Blalock, 150 miles. Was named after Dr. Nelson G. Blalock. There was an O. W. R. & N. station and 2 large warehouses there. The station was 600 to 1,000 feet from the boat landing which was said to be a good landing on a gravel slope that was 100 feet to the top of the bank. Blalock had no settlement but the farmers from the surrounding area talked about constructing a warehouse. There was no development of the river bench, but it was laid out for orchard tracts. Wheat country on the hills and a wagon road ran from the hills down to the railroad warehouse.

Arlington, 137 miles. The shore had a boulder beach and large boulders needed to be removed to make a safe landing. There was a large amount of wheat and wool raised in the back country and there was a good wagon road leading to Rock Creek and Condon. Today this road is known as Highway 19 or the John Day Highway.

Heppner Junction, 146 miles. The boat landing was close to the railroad embankment. There was no road. In 1915 plans were made to build a highway from Heppner Junction down Willow creek, which would give an outlet for Morrow county. The road would be constructed and was called the Oregon-Washington Highway in 1934, and ran down Willow creek canyon to Heppner. Today it is known as the Heppner Highway or Highway 74. The John Day dam submerged almost 2 miles of the highway at the mouth of Willow creek, and the 3 miles of road which wasn't submerged is now part of Willow Creek Road. This road merges with the Heppner Highway which was rerouted away from the canyon about a mile west from where Heppner Junction used to be.

Castle Rock, 156 miles. Castle Rock was a low bluff which was said by those traveling on the river that it resembled a castle. The town of Castle Rock was platted in 1883 and had a depot, steamboat landing, post office, a stage coach stop and express office, saloons, a school and residences. When the railroad built its new line further inland the town began to fade and in 1926 the post office closed. In 1940 Castle Rock had a population of 10 and in 1971 the town was submerged by the John Day dam.

Irrigon, 174 miles. The 1917 report said that with good roads wheat that went from lone and Lexington on the Heppner branch could be hauled with advantage to this point. Irrigon in 1917 had a good place for a boat landing. Umatilla, 181 miles. the 1917 report said Umatilla had a good boat landing and was a natural outlet for the Pendleton country.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition Travel Down the Columbia

The Columbia river between Umatilla and Biggs had 12 rapids. These rapids were submerged by The Dalles dam, The John Day dam and the McNary dam. On October 21, 1905 the Oregon Daily Journal reprinted a passage from the Lewis & Clark diary dated October 21, 1805 about their journey down these rapids from Umatilla to Biggs; "October 21; The morning was cool and the wind was from the southwest, At 5.5 miles we passed a small Island; 1.5 miles further, another in the middle of the river, which has some rapid water near its head, and opposite its lower extremity 8 cabins of Indians on the right side."

"We landed near them to breakfast, but such is the scarcity of wood that last night we had not been able to collect anything except willows, not more than barely sufficient to cook our supper, and this morning we could not find enough even to prepare breakfast. The Indians received as with kindness and examined everything they saw with great attention. In their appearance and employments, as well as in their language, they do not differ from those higher up the river."

"The dress is nearly the same, that of the men consisting of nothing but a short robe of deer or goat skin, while the women wear only a piece of dressed skin, falling from the neck so as to cover the front of the body as low as the waist, and a bandage tied around the body and passing between the legs, over which a short robe of deer or antelope skin is occasionally thrown; Here we saw two blankets of scarlet and one of blue cloth, and also, a sailor's round jacket; but we only obtained a few pounds of roots and some fish, for which we of course paid them."

"Among other things we observed some acorns, the fruit of the white oak. These they used as food. either raw or roasted, and on inquiry informed us that, they were procured from the Indians who live near the Great Falls, (Celilo). This place they designate by the name very commonly applied to it by the Indians snd highly, expressive, the word "Timm" which they pronounce so as to make it perfectly represent the sound of a distant cataract. After breakfast we resumed our journey, and in the course of three miles passed a rapid (Owyhee), where large rocks were strewn across the river, and at the head of which on the right shore were two huts of Indians."

"We stopped there for the purpose of examining it as we always do when any danger is to apprehended, and send around by land all those who cannot swim. Five (?) miles further is another (Rock creek) rapid, formed by large rocks projecting from each side, above which were five huts of Indians on the right side occupied, like those we had already seen, in drying fish. One mile below this is the lower point of an island close to the right side, opposite which on that shore are two Indian huts."

"On the left side of the river at this place are immense piles of rocks, which seem to have slipped from the cliffs under which they lie. They continue till, spreading still further into the river, at the distance of a mile from the island, they occasion a very dangerous rapid (Squally hook), a little below which on the right side are five huts. For many miles the river is now narrow and obstructed with very large rocks thrown into its channel; the hills continue high and covered, as is very rarely the case, with a few low pine trees on their tops."

"Between three and four miles below the last rapid occurs a second (Indian), which is also difficult, (Indian rapids was named in the early days of river navigation from the fact that there Captain Baughman lost 2 Indian crewmen by the wrecking of his sailing Scow.) and three miles below it is a small river, which seems to rise in the open plains to the southwest and falls in on the left it is 40 yards wide at its mouth, but discharge only a small quantity of water. We gave it the name of Lepage's river, from (Baptiste) Lepage, one of our company. Near this little river (now known as the John Day) and immediately below it we had to encounter a new rapid."

"This river was crowded in every direction with rocks and small rocky islands, the passage crooked and difficult, and for two miles we were obliged to wind with great care along the nar row channels and between the huge rocks. At the end of this rapid are four huts of Indians on the right and two miles below five more huts on the same side. Here we landed and passed the night, after making 33 miles. The inhabitants of these huts explained to us that they were the relations of those who live at the great falls."

"They appear to be of the same nation with those we have seen above; indeed, they resemble in everything except that their language, although the same, has some words different. They have all pierced noses. These people did not however, receive us with the same cordiality to which we have been accustomed. They are poor; but we were able to purchase from them some wood to make a fire for supper, of which they have little, and which they say they bring from the great falls."

"The hills in this neighborhood are high and rugged, and a few scattered trees, either small pine or scrubby white oak, are occasionally seen on them. From the last rapids we also observed the conical mountain toward the southwest, which the Indians say is not far to the left of the great falls. From its vicinity to that place we called It the Tlmm or Falls mountain. The country through which we passed is furnlshed with several fine springs, which rise either high up the side of the hills or else in the river meadows, and discharge themselves into the Columbia."

"We could not help remarking that almost universally the fishing establishments of the Indians, both on the Columbia and the waters of Lewis river, are on the right bank. On inquiry we were led to believe that the reason may be found in their fear of the Snake Indians, between whom and themselves, considering the warlike temper of that people, and their peaceful habits. Its very natural that the latter should be anxious to interpose so good a barrier."

"These Indians are described as residing on a great river to the south, and always at war with tne people of this neighborhood. One of our chiefs pointed out today a spot on the left where, not many years ago, a great battle was fought in which many numbers of both nations were killed. We were agreeably surprised this evening by a present of some very good beer, made out of the remains of bread, composed of the pashecoquamash, part of the stores we had laid in at the head of the Kooskooskee, and which by frequent exposure becomes sour and molded."

The Deschutes River to Pendleton in 1907

On June 25, 1907 the Oregonian printed an article about the city of Pendleton asking the Railroad Commission for a local passenger train to be put on between their town and Portland. The city said that the through west bound trains were usually delayed and overcrowded when they reached Pendleton. They also said the coaches were dirty and the bathroom was filthy. The citizens of Pendleton said that they could not be sure of any certain time of leaving their town, or when it would arrive in Portland under the present circumstances.

They asked to have the Biggs local extended to Pendleton which would give them regular service to Portland. The railroad said that service to Pendleton was adequate and that all passengers were provided with seats per the rule, and they also said the coaches were clean as was practicable for them to be kept after the long journey from Portland. They then said that owning to the thinly settled country east of Biggs, the extension of the Biggs local would not make them any money.

After hearing some witnesses who were placed on the stand by the railroad company, the commission took the case under advisement. J. H. O'Neill who was a traveling passenger agent for the O. R. & N. said that since 1899 some sections of the system travel were lighter than in years past. He said many farmers had sold out to large wheat growers. The witness said he had traveled on trains 1, 2, 5 and 6 a great deal, and with few exceptions, he noticed that everyone who wanted a seat was able to find one.

He then said that; "on these trains, there were toilet conveniences, owing to an order a short time ago to provide wash towels in the toilet-rooms, and this service is done at the terminals and at Pendleton and La Grande, which are not terminals." He continued saying that while towels were practically always available, people sometimes removed them from the cars. He finished his testimony by saying that the railroad could add another passenger coach when the train arrived at Pendleton instead of putting on another train.

W. Dunn who was a conductor said the population of the little stations west of Pendleton amounted to practically nothing, which added but little to the passenger earnings of the company. He said Barnhart and Yoakum stations were two stations where there was very seldom a passenger. At Nolin the witness said there was one resident, a farmer named Slusher, and his family, and Mr. Slusher bought about all the tickets which were sold at Nolin. At Willows, Conductor Dunn said, there was no traffic offered, as well as at Fosters and Coyote.

Castle Rock and other places a stray passenger was the exception. "Nobody there." said the witness, when asked how prolific Quinton was with ticket purchasers. At Blalock's he said there was a little business, but this was so small that it would not reach one passenger a day. At John Day there were said to be no passengers, while at Squally Hook a lone passenger occasionally got on or off. Commissioners Atchison and Campbell reminded the witness of a trip made over the line on June 5th, when the toilet rooms were said to be in a filthy condition on Conductor Dunn's train.

Dunn did not recall the specific instance but admitted that in many cases it took only from 5 minutes to an hour for passengers to litter up a train. The witness said that while the Biggs local sometimes got mussed up, it was a different muss from that found on the overland trains from the East, where passengers had been in the cars for 3 days. In answer to a question from A. C. Spencer, attorney for the O. R. & N., who examined the witnesses for the defense. Conductor Dunn said that passengers had to stand up very rarely because of a lack of seats. He said, however, that many often stood from choice.

On July 26, 1907 the Eugene Daily Capital Journal said that the railroad made a rule to hold the Heppner and Condon branch trains for an hour and 30 minutes for train No. 1 when they had passengers. They also arraigned to take the Heppner branch passengers to Arlington promptly on arrival at Heppner Junction, whenever No. 1 was over 2 hours late. They also arraigned to place a clean coach on No. 1 at Pendleton to handle local passengers west from that point to Portland and made similar arraignments as train No. 5 was concerned, as long as it could be done without badly delaying the train in picking up a car a Pendleton.

The Old Route from the Deschutes River to Pendleton

Before the Columbia River Highway was extended to Umatilla in 1920 the route followed the old stage road to Wasco. After crossing the Deschutes this road turned to go up Fulton canyon for about a mile and then it turned left and followed Frank Fulton canyon to Welk road, and followed this road to Oregon State Highway 206 where it merges with Welk Road at Sand springs. This was the site of Price's Stage Stop. From Wasco the old route followed the Old Wasco-Heppner Hwy to Klondike and then to the John Day river crossing at McDonald.

This crossing was a short distance south of the Oregon Trail crossing of the John Day river. This was where Leonard's bridge had stood. In the 1910's to cross the river a ferry was used although it was not able to operate in the late summer when the river was low. Cars would then have to ford the river and take their chances or pay the owner of the ferry $2 to have his horses pull you across. After crossing the ferry the route continued on to Rock Creek and then to Olex, and followed Ione road to the town of Ione. Another route followed the Oregon Trail between the John Day crossing and Echo.

From Ione the route followed up Willow creek to Lexington. Here the motorist had 2 routes which they could take; the left route continued to Echo which they could drive north to Umatilla or they could turn south to Pendleton. The other route continued southeast on what is today Highway 74 to Heppner, and then to Nye where Highway 74 meets Highway 395. The route then followed Highway 395 in a northeast direction to Pilot Rock and finally reaches Pendleton. The old highway between Heppner and Pendleton was a section of the Blue Trail. In 1920 before the Columbia River Highway opened you could take another road from McDonald's crossing and travel north to Arlington.

Greatly Excited When Car Arrives

In the June 26, 1910 issue of the Oregon Journal is an article about the first car to be driven into Ione, Oregon. The writer said it was an interesting and remarkable trip from The Dalles to lone. The car was driven by F. G. Plummer who was an employee of the Northwest Buick company and Frank Parker. In places they had to traverse deep sand and many hardships were encountered, but in spite of their difficulties the distance of 90 miles was covered in 6 hours, (Today it would take you about an hour and a half to drive the 90 mile route from The Dalles to Ione.)

They averaged 15 miles an hour and said that speed was unusually high considering the condition of the roads. "When we entered the town of Ione," said Plummer. "we immediately became the center of attraction of the whole town. This was easily accounted for, as I understand we were the first car to enter this place. We then drove out to the ranch of L. C. Davidson, 25 miles from Ione, and there we found several men who have never seen an automobile. We drove all over the wheat fields."

The Davidson ranch contained 12,000 acres and 8,000 was used for growing wheat. They then said they were served a meal which was the best they ever had in their entire lives. Plummer then said that; "We encountered on the road a lot of deep sand which impeded our progress considerably. Owing to the fact that the John Day river is too low this time of year for the ferry, which is used at the crossing during the winter, we were forced to ford the stream. This was a rather thrilling experience because we were not sure of the depth of the water. The farmer who owns the ferry charged $2 to tow the machine across with a team of horses."

"Over the John Day river, enterprising automobilists or the county could well afford to build a bridge. The distance is only 150 feet across and the bridge could be constructed at a cost of about $500. Just now it is a case of fording the river or not crossing. The water is too deep to permit a car to cross with assurances of safety. There is a great need of sign boards along the road. As the directions have to be guessed. There is considerable danger of becoming lost. The weather during the time we were making the trip was all that could be desired. It was neither too cold nor too hot. There was but one small shower."

Portland to Pendleton in 1913

In the August 21, 1913 issue of the Oregon Journal is an article written by Francis C. Jackson about a trip he and some others took from Portland to the Pendleton Round-up. Jackson said they drove over the Barlow road and those who were fortunate to get through without trouble gave high praise of the route. Those who had tire troubles were loud in in their condemnation of the road condition. Jackson commented that; "the worst howling was heard from the fellow who tailed another automobile and could not get up quite enough speed to pass the car in front and did not know enough to drop back to a position that would allow the dust to settle. The majority of those who made the trip seem to be of the opinion that the Barlow road to eastern Oregon is an easy and pleasant route."

Their return trip was by way of Pilot Rock, Heppner and Lexington. They said that the road through this section was in fair condition. From Lexington to Ione, the road was good and there was a delightful little hotel in Ione. The proprietor did his own cooking and the meal they had was the best of their trip. From lone to Olex and through Wasco the roads were bad until they hit the Deschutes river.

The old road to The Dalles was one of the best dirt roads they ever encountered on a touring trip. Jackson said; "Crossing the Deschutes over Miller's bridge, noted for its picturesque and historical interests, we climbed the hill that overlooks the Columbia and the scenery from this point is as good as any found in any part of the world. Before descending the canyon to Miller's bridge it is noticed that the road passes through private grounds instead of following sand stretches along the river."

"The roads are well kept and several gates have to be opened as the descent is made. Miller's bridge is rich in historical interest on account of its being the crossing place for the stage coaches of the early days. The scenery into The Dalles is beyond comparison. The roads through this rich country are in very good condition. From The Dalles to Hood River the scenery is wonderful. The road, however, along the cliffs is very steep with long grades and few passing benches."

"Many making this trip are of the opinion that Multnomah county is foolish to spend an immense sum on the Columbia River Highway from Portland to Hood River unless Hood River interests will guarantee to cut down the grades between Hood River and The Dalles in order that the commercial value of the road may be assured."

A Trip from Pendleton to Wasco in 1917

In 1917 there was more than one way to reach Wasco from Pendleton. One of the old roads followed the Oregon Trail and in the November 18, 1917 edition of the Oregonian is an article about a trip that L. M. Thielen and his wife took from Portland to Moscow, Idaho. The following is a description of their trip back to Portland between Pendleton and Wasco. They covered the 150 miles from Moscow to Pendleton, via Walla Walla the first day and said the roads were excellent.

This was more than they felt able to say of the roads between Pendleton and Wasco, their second night's stopping point. Some distance out from Pendleton they struck the desert country, and for 50 miles their way led through it. The road was sandy and dusty and full of potholes left by heavy wheat wagons. They also encountered badger holes. It was such hard going that for almost this whole distance they were in low gear. They said that even this dreary landscape was not without its points of interest for the tourist. The road they took followed the old Oregon Trail, which was marked by concrete posts.

The pioneers did not have the advantage of the automobile and traveled it behind plodding oxen. They were happy when they arrived at the village of Cecil, which was surrounded by alfalfa fields and contained a gasoline station. They said the place was an oasis in this desert. They were relieved when they reached it as they only had about two gallons left. At the John Day river they paid $1 to be ferried over. Later in their trip they paid $1 to see probably the last surviving curiosity of its kind, the rickety old toll bridge across the Deschutes river.

They said that; "some day the toll bridge would be eliminated and at present it stood as a sort of last frontier against the surrounding civilization. Surprised tourists from as far east as Massachusetts who have to pony up their dollars to cross the river on this rattling structure console themselves with the remark that it is the only relic of its kind they have met in the whole course of their transcontinental journey." After spending the night at Wasco, the Thielen's had plenty of time to drive to The Dalles and make the Portland boat, but they didn't know the highway between there and Portland was closed for construction work, so they did not hurry. They reached The Dalles at 12:25pm, which was 25 minutes too late for the boat, and they had to stay there overnight to catch the next day's boat for the remainder of their trip back home.

The New Route from the Deschutes River to Pendleton

After the Columbia River Highway was completed in 1921 travelers leaving Biggs followed along the current Highway 30 eastward to Rufus, although much of the old highway is now between the current road and the railroad tracks. When you arrive in Rufus you are driving on the old roadway. After leaving Rufus the old road follows on Frontage road and then disappears under the freeway and then runs through the southern boundary of French Giles park before it becomes submerged by the John Day dam which was completed in 1971.

Between the John Day dam and Arlington the old road is mostly underwater. This section of the highway travels through a sparsely settled area. Before the dam was built there were 5 stations along this section of the highway. From Rufus traveling east the first stop was about 4 miles away called John Day. There was never any settlement there and today you would never know the trains would stop there to pick up the occasional traveler.

The next place traveling east was called Goff which was on the east side of the John Day river and was about 2 miles from the John Day stop. There is little information about Goff station although in the Oregon Statesman issued on February 3, 1920 is an article about a trip that Herbert Nunn the Oregon State Highway Engineer took between Portland and Umatilla. He said the new highway between Echo and Willows creek was in excellent condition. and cars could travel very fast over it. At the John Day river he found the bridge had been completed which cost $28,000, and that when the approaches were completed and the bridge opened for traffic would eliminate the need of taking the ferry at Goff station 30 miles east of The Dalles. The bridge was 250 feet long with approaches of 200 feet.

After Goff station was the Squally Hook station which took the name of the rapids which were encountered by people traveling on the Columbia. Squally Hook was about 5 miles upriver from the mouth of the John Day. Next was an old wheat shipping point called Quinton which was also referred to as Quinns and is about 3 miles upriver from Squally Hook. After Quinns is Blalock which is about 7 miles upriver from Quinns. Further upriver about 8 miles you arrive in the town of Arlington.

After leaving Arlington the next stop on the railroad was Willows station which was 9 miles upriver from Arlington. At 10 miles is Heppner Junction and the road to Heppner. About 4 miles upriver from Heppner Junction and the mouth of Willows creek you arrive at Boulder station where a ferry used to operate across the river to Alderdale. About 5 miles upriver from Boulder was the town of Castle Rock which today is underwater. Another 4 miles upriver was a stop called Peters. Only a mile and a half upriver from Peters you arrived at Old Boardman. After the John Day dam was completed the town of Boardman was submerged and the town moved about a mile to the east.

From Boardman to Irrigon the Columbia River Highway is called Columbia Boulevard. and Columbia Lane. Between these roads the highway is now the Morrow County Heritage trail and is only for bicycles and pedestrians. Between Irrigon and Umatilla the road is now a section of U. S. Highway 730. Going south from Umatilla to Hermiston the highway is called County Road 1275. From Hermiston to Echo the road is U. S. Highway 395. And From Echo to Pendleton it is now called Reith Road.

Today of the 85 miles of the Columbia River Highway between the Deschutes river and Umatilla, about 40 miles of the original roadbed is now underwater and about 8 miles is under the freeway. About 20 miles of the old highway can still be driven on, though most of these sections have been modernized. East of Boardman there is a section 1.25 miles long of original highway which is now called the Morrow County Heritage Trail, which is for pedestrian and bicycle traffic only. Almost a mile of the original roadway is used for railroad access and is gated (Woelpern Rd.), and the rest of the original roadbed is either obliterated or is not a part of any current road or highway and lies abandoned.

Most of these abandoned sections still retain the original pavement. In many places it is just a small piece of roadway among the grass, brush and sand. There is a long abandoned section which begins 2 miles east of Arlington and is about 3 miles long. This segment is visible from a satellite map. This abandoned piece lies between the railroad on the north and the freeway on the south, and may be accessible to hike on, although it is unknown to me if it is open to the public.

Eastern Extension of the Highway is Urged

In the August 27, 1916 Oregonian is an article about the need to extend the Columbia River Highway into Eastern Oregon. They said that the impression in some of the sections east of the Cascades that the Hood River people were apathetic over the proposed improvement of the east extension of the highway and were refuted by the very action of local motorists, who were each week of that summer taking trips through eastern parts of the state.

The newspaper said that it should have been

natural that Hood River citizens, because of their geographic location, should have been interested

more keenly back then in the completion of the scenic river route between eastern

Oregon and Portland, there was a realization in all minds that the Columbia River Highway,

as swiftly as funds were available and the work was feasible, should be pushed through the eastern part of the

state to connect with the branch of the Lincoln Highway at Ontario on the Snake river.

"The construction of this link of the transcontinental road between Hood River and

the eastern part of the state not only would be a great benefit to Hood River,"

said E. O. Blanchar, who was a cashier of the First National Bank, in Hood River, who, with

his wife, and Mr. and Mrs. A. D. Moe, and C. Dethman, returned recently from a

3 day tour as far east as Spray on the John Day river. He then said; "but it will be a

big factor in the development of the fertile communities of the eastern interior."

"It is gratifying to find road interest running so high in eastern Oregon. Over there the phase presented by great scenic highways, which is perhaps uppermost in our minds, is overshadowed by the benefits that will accrue to the road builders from making their communities more accessible to outlying markets. In the heart of the agricultural section of eastern Oregon, and the great wheat fields of Sherman county, road work is going forward rapidly. There the authorities are putting their highways in first class shape. It is a pleasure to travel through Sherman county."

"Down in the John Day valley are some of the most fertile communities of the state. In the near future great development is going to take place there. The rich soil can be made to produce a great variety of crops. However, up to the present time, because of isolation, the John Day district has been devoted to stock raising to a large extent. So greatly are the citizens of Wheeler county interested in the construction of better roads that by private subscription they are matching funds appropriated by the County Court to raise money for surveys of trunk roads. They will undoubtedly vote a bond issue at the coming Fall election, having been assured of state aid in the event of the bond election carrying. Between Condon and Fossil construction of a better road down the great canyon running north and south is now in progress. The state is spending $30,000 on this project."

Sometimes it Takes a Woman or in this Case a Group of Women

At the beginning of 1917 the Columbia River Highway had yet to be extended east of The Dalles. In the Oregonian on January 19, 1917 it said that Umatilla elected Laura J. Starcher as its first woman mayor. The city council was also comprised of a majority of women with only 2 men. The women of the council were; Anna Mecas, Florence Brownell, Bertha Cherry, recorder; Tella Paulu, Gladys Spinning, treasurer; and Mrs. Robert Merrick. They were said to have started out in the most determined manner and were likely to get results.

At their first meeting the city budget was cut by $57 and they ordered 16 new lampposts to be installed, as the former council had some of the lights taken out. They also ordered a cleansing of the City Hall and proposed a repair of the same, and then they decided that they will have to move to new quarters. Councilman Stephens contested the authority of the mayor to not appoint a marshal which saved the city $57 a month. When Councilman Stephens protested the move the mayor shushed him up and he stopped his arguing. She said that Umatilla was a peaceful city and that there was a deputy sheriff available for police duty at all times, and the city ordinances empower any member of the city council to make an arrest, she did not deem it necessary to encumber the city payroll with an additional official.

Alter a long discussion a resolution was adopted about the various proposed routes of the Columbia River Highway east from The Dalles. The council decided that Umatilla should work with all the other towns from Arlington to Pendleton on the O. W. R. & N. main line to try to get the highway built their way. The resolution read;

Whereas, There is before the Legislature at this time a bill providing for the State Highway Commission to be empowered to lay out the route for the Columbia River Highway from The Dalles east; and,

Whereas, Several routes have been proposed. It is a noticeable fact that all the proposed routes which have been mentioned by newspapers have been laid out over a rough and hilly country and many miles back from the Columbia river, for which the highway is named; and,

Whereas, The Columbia River Highway can be built from The Dalles east along the Columbia river by way of Arlington, Boardman, Irrigon and Umatilla, thence through Hermiston, Stanfield, Echo, Nolan and Rieth to Pendleton on a true water grade, with the minimum expense for construction, and serve more people than any other possible route back away from the river, it also would draw all tourist travel from eastern Washington and Montana points to Portland; and,

Whereas, A water grade can be had from all points on other proposed routes to the Columbia river, and this proposed route; be it,

Resolved, by the city of Umatilla, That the Columbia River Highway be routed as herein described, which is the only real Columbia river route; and be it further Resolved, That a copy of this resolution be sent to the state Highway Commission, the Governor and the press.

Water Grade for the Highway was strongly Urged

In the July 15, 1917 issue of the Oregonian is an article about the extension of the Columbia River Highway east of The Dalles. On Tuesday July 10th at 2pm the Cooperative Columbia River Highway association met in Portland to devise ways and means for construction of the highway. An invitation was extended to the State Highway Commission and the county commissioners of Sherman, Gilliam, Morrow and Umatilla counties to be present.

The Cooperative Columbia River Highway association was formed at a meeting in Portland, called by Mayor Clay C. Clark of Arlington, and others interested in building the Highway along the south bank of the Columbia on a water grade. Delegates were present from the towns of Biggs, Rufus, Arlington, Boardman, Irrigon. Umatilla. Hermiston, Stanfield and Echo. The purpose of this association was to aid in the building of a highway from The Dalles, through Biggs, Rufus, Blalock, Arlington. Heppner Junction Castle, Boardman, Irrigon, Umatilla, Hermiston, Stanfield and Echo to Pendleton.

The officers of the association were; Clay C. Clark president; E. R. Dodd, secretary treasurer, and D. C. Brownell, vice president. It was declared by this association that the state bonding act, which provided for the construction of this highway could not have passed with any other route as a primary highway. They said that construction per mile would be 30% cheaper, because water was convenient, sand and gravel was on the ground and transportation facilities for other materials were available at the lowest rates by rail and water. Maintenance of a water grade road they also said, would be 50% less. It was estimated that the saving by the water grade route would be as much as $200,000.

Wasco on the Columbia River Highway?

In the Fall of 1917 there was talk of diverting the Columbia River Highway inland and connect it with the town of Wasco. Others said it would be too expensive and costly to commercial interests due to the climb up the hill to reach the town. In the November 4, 1917 issue of the Oregon Journal they said that from the standpoint of construction cost, it was estimated that it would involve an additional expense of approximately $100,000 to divert the Columbia River Highway through Sherman county from the river into the interior by way of Wasco.

The proposed interior route was approximately 9 miles longer. Although the cost of grading the river route might have been equal to that of the interior route or a little in excess, the hard surfacing of the extra 9 miles would make the ultimate cost of the interior route that much greater. Besides the increased distance there was to be figured in the extra cost of hauling water and other material. Another factor which was to be taken into consideration was that the interior route would require an uphill haul to an elevation of 1,000 feet. Wasco is 1,200 feet above sea level, while the river is 200 feet.

Through travel by the interior route would not only be required to go a farther distance, but would be compelled to spend an extra amount for power consumed in the uphill haul. There would be some justification for the interior route if Wasco had no outlet to the river. But this was not the case as the state had already constructed a good road at an expense of $40,000, down Spanish Hollow to Biggs and then south to Wasco a distance of 10 miles.

In addition, there was a county road down Fulton canyon (The old stage road) coming out to the river near Sherman. It is not so good a road as a state road and the old route never could be made so, for the reason that the canyon is much more narrow and rugged than Spanish hollow. (In the 1930's Highway 206 would be completed through Fulton Canyon to Wasco on a slightly different route.) The newspaper said that logically, Wasco should be on the highway running from the Columbia river south to Lakeview, which they said would become the main north and south road through Central Oregon, connecting the Washington and California systems. They were almost correct as Lakeview is now on Highway 395 and Wasco is on Highway 97 which are both north south highways through eastern Oregon.

The Water Route is Chosen for the New Highway

In the July 13, 1919 issue of the Oregon Sunday Journal is an article written by R. C. Johnson about the importance of the Columbia River Highway. In 1919 the route of the highway had been decided and it was to run along southern bank of the Columbia as it should and the terminus of this great thoroughfare was to be at Umatilla, where it would join the Oregon Trail for the remainder of the route to Pendleton. Johnson said that the road would be extended to the state boundary, where it would connect with the Washington roads at Wallula. (This route would become the Wallula cut-off which was completed in 1922.)

Johnson then said that the Columbia River Highway was more than a state highway, It was a Washington highway as well as an Oregon road which furnished an all year route of travel between eastern Washington and western Washington as it does between the eastern and western portions of Oregon. Through one of its laterals, the old Oregon Trail, reaches into the Snake river valley and becomes an Idaho road. Therefore properly it may be defined as a joint-state road.

It was generally spoken of as a great scenic highway and as such was deserving of the reputation it bore. Its scenic setting however, was but incidental to its importance as a great artery of commerce. With its branches reaching up the canyons and draws of the great Columbia river basin and extended into the food producing region of the Northwest. Within it is the potential power of transporting to the banks of the great river of the west the products of an empire through which it distributes in return the supplies and manufactured products the inland empire consumes.

As a commercial instrument the Columbia River Highway supplements the "open river" and makes complete the great system of transportation which lies on the horizon of realization, the component parts of which are river, highway and railway. The open river which has been long dreamed of can never be fully realized until there is joined to it the Columbia River Highway system. It is for this reason that in locating the highway the river has been the point of control.

Johnson said that; "It is but a few years since the Columbia River Highway was transferred from the minds of men of broad vision to paper. It will be but a few months until it has altogether passed from its paper existence into a thing of life and beauty. Through the forest, around the rock base of mountains, under towering cliffs and between dunes of sand there will soon be a broad paved highway on nearly a water grade from the shore of the Pacific to the mouth of the Umatilla."

"It is not unreasonable to predict that by the fail of 1920 there will be a paved highway all the way from Seaside to The Dalles and a macadam surface from that point to Umatilla. The work on the Sherman and Wasco units of the highway has been delayed by negotiations with the' railroad company and the federal government for right of way where there was an encroachment on the railroad track and around the Celilo locks. This is in a fair way of adjustment and within, a few months it will be possible to put those units under construction."

"From The Dalles eastward the highway will continue along the river past Seufert and the Celilo locks under the bluff to Arlington and on to the mouth of Willow creek and thence to Umatilla. From a scenic standpoint the highway beyond The Dalles, with the exception of the view at Celilo, will lose its varied interest. But it is here that its character as a factor in future transportation becomes most apparent. At The Dalles there comes into it by way of Dufur The Dalles-California highway which brings to the river all the traffic of the Deschutes valley and provides an outlet for Klamath and Lake counties."

"The great wheat fields of Sherman county, will pour their yield into the highway and thence to the river by way of Fulton canyon and Spanish hollow. At Grants, Rufus and Blalock are other laterals reaching back into the interior. The products of Gilliam county find their way to the highway and river at Arlington. Morrow county's outlet is down Willow creek and at Umatilla is centered the traffic of Umatilla county and northeastern Oregon. Across the river on the Washington shore are also stretches of road reaching back which will, feed into-the Columbia river system of highway and waterway."

"Going back to Sherman county there will some day be a main trunk highway running through the center of the county, from Biggs, through Wasco, Moro, Grass Valley and Kent and on to Shaniko, Prineville, Lakeview and thence to the Sacramento valley." This Highway did become a reality and is now known as U. S. Highway 97.

Construction Begins

The Columbia River Highway followed the Columbia river gorge through the Cascade mountains passing through Hood River, Mosier, The Dalles, Biggs, Rufus and Arlington, thence along near the river through Heppner Junction, Boardman, Irrigon and to Umatilla, which marked the and of the highway. At Umatilla the Columbia River Highway ends and the Old Oregon Trail begins. This part of the highway was to be something of a scenic road as well as providing favorable alignment and an almost water grade. In the 1920's or 1930's the road between Umatilla and Pendleton would became an official part of the Columbia River Highway

Near Quinton in Gilliam county was to be a tunnel 522 feet In length. This tunnel was to pass through a rock cliff with a vertical face and which condition would have allowed windows to he excavated in the solid rock for the purpose of lighting the tunnel. This tunnel would not be constructed. In Wasco county there will he two tunnels of shorter length through solid rock paralleling the river. (the Twin tunnels at Mosier) The construction will also involve two large bridges. Over the Deschutes river would be a bridge built of concrete and steel combined.

At the Deschutes river crossing the traveler was afforded an unusual view. The bridge had the appearance of a concrete structure, and it spanned the stream directly over the rapids. This structure cost about $100,000 and construction began in the summer of 1919 and was completed in the summer of 1920. This structure was removed before The Dalles dam was completed in 1957 and was located between the current railroad bridge and the current hwy 30 bridge. At the John Day river a timber bridge was constructed. This structure was built on concrete piers so that the bridge could be replaced by steel. The bridge would be replaced in later years and was submerged in 1971 by the John Day dam.

The total length of the original highway from The Dalles, to Umatilla was 101 miles. The survey and construction plans for the entire distance had been completed in the summer of 1919 for the grading of the road. The road for the entire distance except for 14 miles was under contract that year. These contracts provided for the grading of the road and a provision was made for the graveling of approximately 33 miles. The contracts let totaled an expenditure of $1,456,000. The amount required to finish the grading and surfacing of this section was approximately $485,000. The contract for the completion, of the 14 miles of grading and the construction of the Deschutes bridge was let in October of 1919.

Progress Was Moving Along Fast

On April 11, 1920 the Sunday Oregonian printed an article written by Lewis McArthur about the progress on the Columbia River Highway. He said that in the fall of 1920 it would be possible to drive the entire length of the new road and said it had taken more than 8 years to put the highway on the map. For its entire length from Seaside to Pendleton the highway was now permanently located and was either completed or under construction. The Columbia River Highway would soon be hard surfaced from Astoria to Hood River, 174 miles, and graveled from Hood River to Pendleton, 165 miles, with the exception of 4 miles of hard surface at The Dalles and 2 miles just west of Pendleton.

There was 180 miles of hard surface between Astoria and Pendleton, and 159 miles of gravel. More than half the highway was paved by that fall and after winter was over the first project to be taken up was 21 miles of paving between Pendleton and Echo and 24 miles between The Dalles and Hood River, or 45 miles of hard surface in addition to the 180 miles mentioned. From Portland to Pendleton the trip was 234 miles, or about a 10 hour run back in 1920.

Grading between the Deschutes river and the John Day was well under way that spring, but progress was spotty. In some places the grade was completed for a mile or more, and in others it had just begun. This work would be completed by August 1920, when it was to be graveled. The distance from the Deschutes to the John Day was 15 miles. From John Day to Blalock was 15 miles, and very substantial progress had been made in grading, while the John Day river truss bridge had been completed and was ready for use. The contract for graveling this 15 stretch was let in the summer of 1920.

From Blalock through to Pendleton the highway was on its final contracts. The graveling contract was let between Blalock and Arlington 9 miles, and a contract was let in the fall of 1919 to gravel the new grade of 12 miles from Arlington to Willow creek. Concrete structures at Willow creek were under way. From Willow creek to Echo was 51 miles and a fine new macadam road was open for travel all the way. This was an excellent example of a good gravel road and the 51 mile trip was being done in 2 hours every day.

All the graveling was completed from Pendleton to Blalock, 96 miles by late summer of 1920. The grade between Blalock and the Deschutes river, or 30 miles more, was ready for surface at the same time. The work between The Dalles and the Deschutes river was the last section to be completed, and when this section was finished in the fall of 1921 the entire highway from Pendleton to Astoria was ready for traffic.

Upper Highway is Praised

Printed in the Sunday Oregonian on August 8, 1920 is an article about the upper Columbia River Highway where Eugene C. Habel and his wife gave praise to the new road. They said the portion of the Columbia River Highway from Arlington to Umatilla was a beautiful smooth road that followed the course of the river, being little more than a half mile from the waters edge at any point. Habel was manager of the Manley Auto company, who had with his wife, returned back to Portland from a 10 day eastern Oregon drive of 1,160 miles that August.

Luckily for the Habels who were combining a pleasure trip with business, where enjoying the ride in their Hupmobile and happened to run into (figuratively) the county commissioners party which had set out from Arlington to inspect 30 miles of the new road toward Umatilla. They were invited to follow the official party, otherwise they would have had to take the old Oregon (yellow) trail route, which was none too good. Habel said that; "The new road is not yet open to general travel, but the superintendent of construction advised us it would be soon. The macadam surface of the highway has already been rolled smooth and covered with a screening of gray dust and fine gravel. This drive over a fine new road that is now just as good for travel as the main Columbia River Highway was certainly a comfort after the rough, dusty drive from The Dalles to Arlington."

According to Habel his Hup averaged just under 20 miles to the gallon, despite hills, sand and dust, and better than 900 miles to the gallon of lubricating oil. Gasoline was plentiful at all towns east of The Dalles, he said, and he didn't even hear anything about a gasoline shortage which was mentioned in the district around Pendleton. The Habeis had camped out every night on their entire trip.

On the drive eastward Habel drove through Hood River, The Dalles, Arlington, Umatilla, Hermiston, Stanfield and Echo. They returned over a different route where he found "rotten" roads from Pendleton to Heppner, and good roads from Heppner to Prineville, a fine highway over the hills from Prineville to Bend, and he didn't find much to complain about the roads from Bend via Madras, Moro and Wasco to Biggs, where he ferried across to the Washington shore in order to visit Goldendale and then swing back to The Dalles by way of Dallesport, Washington.

In driving to the ferrying place at Biggs, Habel found that motorists were obliged to take a run and jump over the railroad track in order to get over the heavy sand safely. Therefore, he advised motorists to stop and take a good look up and down the railroad track before making the dash which every car was compelled to make. The sand was several inches deep and there was a right angle turn to further complicate the situation. If called to choose between the Heppner and Echo routes out of Pendleton, Habel said his experience over both routes would compel him to vote in favor of the Heppner route, though he frankly said both roads were poor.

The farmers had already commenced to haul wheat over the old Echo-Pendleton road, making high centers, he reported; "and the new road will probably not be opened for some time pending the completion of bridges and new fills." When all of the highway construction that was under way was completed, he said; "the drive through the fascinating wheat country of eastern Oregon will be a real delight to the motorist of western Oregon, who has spent most of their driving days on the western side of the mountains."

Almost Completed

At the end of 1920 the highway in a few places was not yet completed. Between The Dalles and the Deschutes river the construction around Cape Horn was slowing down because a tunnel could not be bored through the bluff and they had to carefully remove the rock so it didn't fall on the railroad. Between the Deschutes and Arlington the road was also not quite ready and motorists were advised to take the old road through Wasco to the John Day ferry and then to Rock Creek where they could turn north to Arlington. This route was rough and muddy in places but passable.

The Columbia River Highway Becomes the Gateway to the Coast

On June 12, 1921 the Sunday Oregonian printed an article written by H. W. Lyman about the Columbia River Highway being the gateway to the Pacific from the Inland regions of Oregon and Washington. Lyman took a trip to the Inland Empire that spring in a Jordan car. The firm of Mitchell, Lewis & Staver, distributors of Jordan, Mitchell and Briscoe automobiles, arranged for the trips The firm had headquarters in Portland and also a branch in Spokane, and it was arranged for Ray Albee, manager of the company at Portland to take the run from Portland to Pendleton, accompanied by the writer, while J. L. Brown, who was manager of the Spokane branch, make the run from Spokane to Pendleton.

The Interstate Commerce commission recognized the Columbia river gorge as the natural gateway from the Inland Empire to the Pacific coast. The auto clubs and other motorists were generally coming to recognize the Columbia River Highway as the natural gateway for motorists from eastern Oregon and Inland Empire points to the western coast. There was a time when there were 3 routes from the Inland Empire points to the coast, which all battled for supremacy; the route over Snoqualmie pass, the North Bank route to Vancouver, Washington, and the road down the south bank of the Columbia to Portland.

But that was in the old days of horse-drawn vehicles. Since then work on the Columbia River Highway from Pendleton to Portland had so surpassed work on either of the other routes that the Columbia River Highway had become recognized as the primary artery through the Cascade barrier. Comfort, beauty, scenery, economy and even time, all dictated that the motorist from the east and the Inland Empire, in making the trip to the coast, use the Columbia River Highway.

From Portland it was but a short jump over excellent roads to the Puget Sound country for those who desired to visit Seattle and neighboring cities. Portland was likewise the logical starting point for the trip down the coast to San Francisco and Los Angeles, and the Pacific Highway, was in excellent condition, and it beckoned the tourist.

In 1921 from the Deschutes river bridge to the John Day river the new highway was as fine a gravel road as you could hope to find anywhere, but beyond the John Day you encountered about 5 miles of rough going. Work also was in progress there, but the road was open. Very rough road with some sand was encountered on this stretch. However, the graveling was going ahead rapidly, and within a short time this entire stretch would be as easy going as that from the Deschutes to the John Day.

When you rolled off the last of the rough roads about 10 miles east of the John Day and again hit the new gravel you could count your troubles as over, for ahead of you for a distance of 100 miles to Pendleton was a new gravel road, a level, smooth road was as convenient and easy to travel as a paved city street. It was only a matter of mathematics on how long it would take you to reach Pendleton. You could run your car at any speed desired up to the legal limit and then figure it out for yourself.

This new highway still follows the river to Umatilla and then follows the northeast bank of the Umatilla river to Pendleton. In 1921 there was a little trouble at Umatilla, due to the fact that the bridge across the Umatilla river there was submerged from backwater of the Columbia. However, a ferry was put in operation at that point and served the purpose during the emergency. This was the only point where any difficulty had occurred or was likely to occur from high water.

To sum it up briefly, Lyman said that the Columbia River Highway from Portland to Pendleton was in excellent condition in 1921 and in better condition than it had ever been. All the difficult road was between Hood River and a point about 5 miles east of the John, Day river, a distance of about 60 miles. Before the middle of the 1921 summer the new grade between The Dalles and the Deschutes river was open and in excellent shape and the grading east of the John Day would be completed. The only paving operations which remained to be completed was between Hood River and The Dalles.

The work would be in progress throughout the entire summer of 1921, and detours during working hours were necessary until the fall. the road from Pendleton to Umatilla, 41 miles was an excellent gravel road all the way. Umatilla to Arlington, 46 miles was also an excellent gravel road. Arlington to Quinton, 15 miles was an excellent gravel road. Quinton to John Cay river bridge 10 miles, the road was under construction with about 5 miles rough and some sand would be encountered.

John Day river to Deschutes river, 15 miles was an excellent gravel road. Deschutes river to The Dalles was 16 miles by the new road and about 20 miles by the old hill road. The new road would be closed until fall because of construction. Motorists were advised to take old hill road. This road was very steep at the Deschutes end with an 18% grade and was rough over the eastern half with last half coming into The Dalles was all a dirt road but it was in fair shape. This old road between Fairbanks and the Deschutes river is still a dirt road but the grade down the hill to the river was made a bit gentler and still is a good road. The view from the bench is spectacular and worth the trip over this historic road.

The Columbia River Highway is Completed

On October 9, 1921 the Oregonian reported that over 65,000 automobile tourists passed through Pendleton during the tourist season which was just closing. This was according to a checker which was placed to record traffic by the Eastern Oregon Auto club, with headquarters in Portland. Over 23,000 cars were counted by daily averages and 2,500 of them parked in the Pendleton auto camp grounds. Washington led all states in the number of cars. Work of the auto club increased so greatly in its first year of activity that it was be maintained all winter so that proper preparations could be made to care for the tourist traffic in 1922.

With the Columbia River Highway open from Pendleton to the sea, a macadam and hard surface highway through Walla Walla to Spokane, and the old Oregon trail from Pendleton into Idaho was to be completed in the summer of 1922. The towns of Umatilla county were preparing for a doubling of traffic. Highway engineers said that the Blue mountains between La Grande and Pendleton could be kept open throughout the year when the old Oregon trail was completed and it would be a stimulus to traffic in eastern Oregon, and the automobile club, which with the American Automobile association. was publishing the news through the United States.

In the opinion of Ernest Crockatt, executive secretary of the club, Oregon will no longer be a state with a short tourist season, but cars will drive east, west and south, the year around.

The Trip to the Pendleton Round-up in 1922

In the summer of 1922 the reports about the condition of the road east of The Dalles was that crews were at work re-graveling portions of the new highway. The road was rough in spots but the surface was in excellent condition and the trip to Pendleton for the Round-up, a distance of 246 miles, could be easily made in one day from Portland. There were no detours on the eastern section of the road. Most or the Portland residents were familiar with the wonders of the Columbia River Highway to Hood River but it was a comparative few who had gone farther east.

The nature of the landscape changes to a rugged and more massive rock formations that are attractive in a different way from the beauties of the highway found at Hood River, but though the eastern parts the scenery is no less beautiful. Within a short distance of Mosier the motorist gets a view of Memaloose island, the old Indian burial ground, while at Celilo, east of The Dalles, the falls were once a picturesque spot on the trip. The grandeur of the Umatilla canyon, through which the road still winds, makes it one of the most attractive parts of the journey.

At Pendleton the motorist was assured of care for there were many garages and hotels. Today is no different. Reservations should be made early though to insure rooms. The automobile camp grounds of that city in 1922 were also available. The camp was of the most modern type and was situated on the east edge of the city. The charge for car space was 50 cents a day.

Sources;

The Columbia a Photographic Journey - http://www.columbiariverimages.com/

The Pacific Northwest Chapter of the National Historical Railway Society - https://www.pnwc-nrhs.org/hs_or_n.html

Historical Mapworks - https://historicmapworks.com/

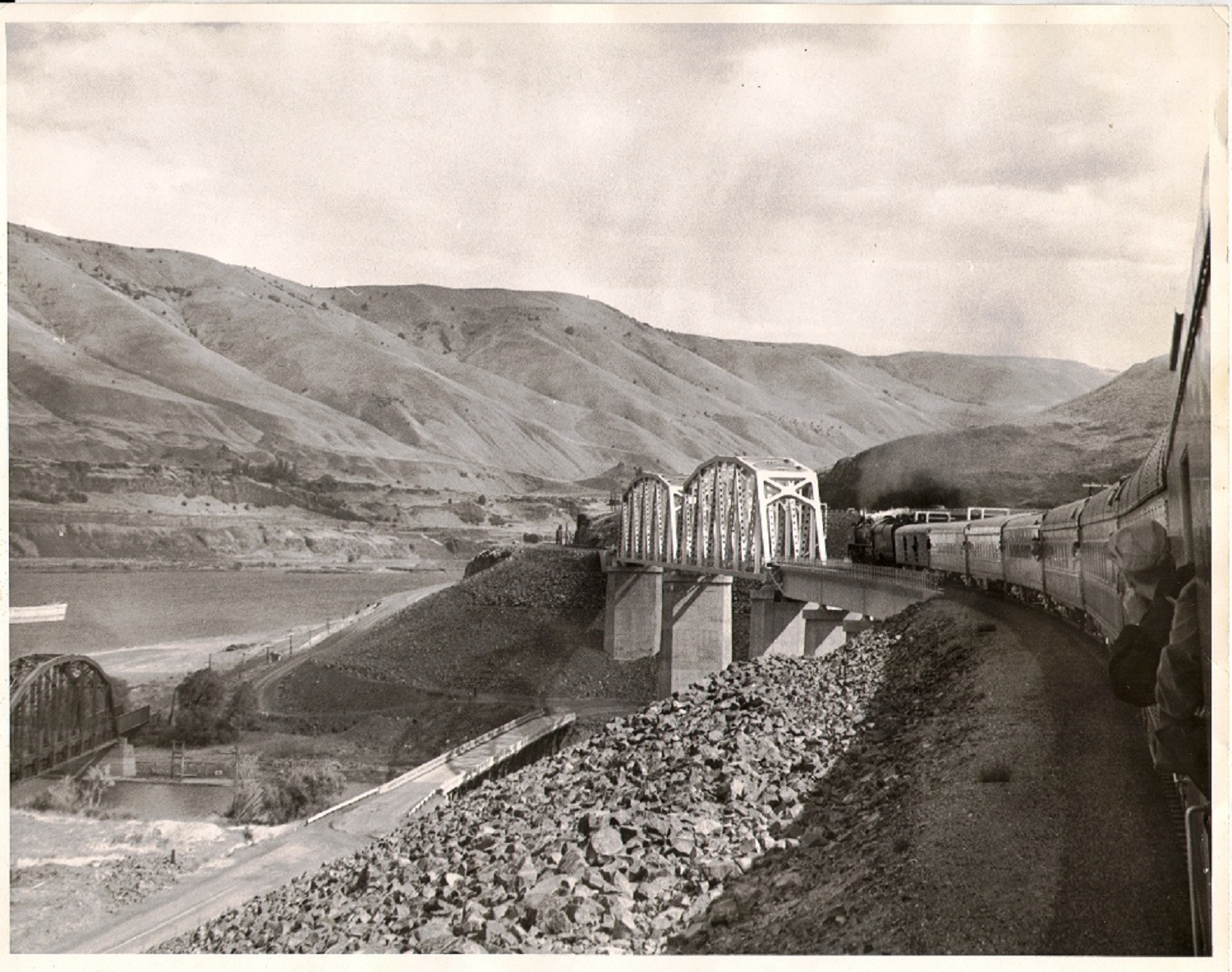

View of the bridges over

the John Day river before the dam was completed. The old Columbia River

Highway crossing below along with the old Union Pacific bridge. The photo

was taken from a passenger train on the new grade which would be above the

rising waters of the John Day dam which was completed in 1971.

Photo courtesy - Wikipedia

The Pendleton Round-up - official site

Some Good Websites about the Columbia River and Highway

The Columbia River a Photographic Journey

Recreating the Old Oregon Trail Highway